Tiny semiconductor chips are essentially the brains powering our modern lives. We use them all day long, in our coffee pots, our cars, our cellphones. But these tiny chips also hold the key to immense economic and government power. Those little silicon wafers help create advanced weaponry and are crucial to national security.

So last summer, in a rare bipartisan move, Congress passed the $280 billion CHIPS and Science Act. They were worried about the country’s reliance on foreign chip manufacturers, particularly in Taiwan, which makes nearly all of the most advanced chips out there. China claims Taiwan is part of China, and if the country were to, say, launch an offensive against Taiwan, the U.S. chip supply would be endangered or cut off. So, the idea behind the CHIPS Act was to reduce our reliance on foreign countries for chip making.

On Sunday’s episode of What Next: TBD, I spoke with Don Clark, who covers the semiconductor industry, about whether the U.S. can really bring chip manufacturing home. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Emily Peck: Through the CHIPS and Science Act, the Biden administration is offering roughly $76 billion in grants, tax credits, and subsidies to incentivize manufacturers to do what’s called reshoring—essentially bringing factories to the states. And chipmakers are responding. Since 2020, more than 35 companies, some of the biggest players in this space, have pledged nearly $200 billion for manufacturing projects related to chips.

Don Clark: It’s an interesting change in industrial policy. It used to be the federal government just built things, but in this kind of a policy, they’re using public money to spur private money. And the reason they’re doing it that way is because that’s what other governments are doing around the world, in Asia and other places.

The idea is to even out the playing field. It’s about 30 percent more expensive with no government support to build a chip factory in the U.S. as it is abroad because of the subsidies and other factors. So they’re trying to basically even it out, so if you’re Intel, it’s essentially neutral as to where you build your plant.

What exactly are semiconductor chips? Explain them to me like I’m 5 years old.

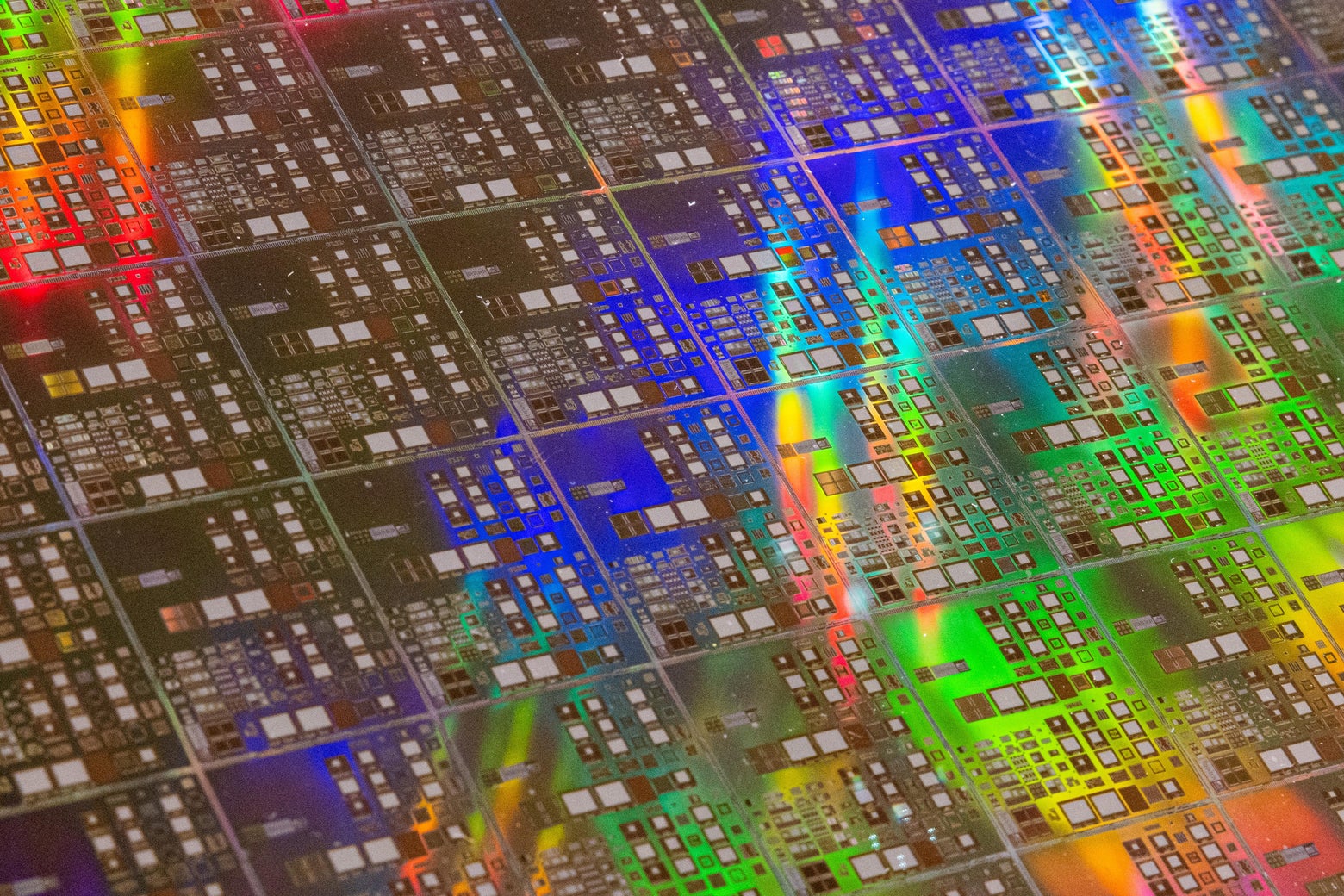

Semiconductor chips are devices that perform all the functions that you want with electrical things. They store data, they add numbers together, they multiply numbers together. They can amplify signals. They can do things like change of voltage. Physically, you take a big wafer of silicon and you photographically put designs on each chip and then they’re broken up into little squares or rectangles.

The famous discussion in Silicon Valley is about Moore’s Law. Gordon Moore was the founder of Intel, and back when he was at Fairchild Semiconductor, he made this prediction about how rapidly companies would shrink the little tiny switching elements called transistors on each chip. And he said they would double very rapidly—every year, every two years—and that has pretty much held true. Chips are one of the few things in life that have gotten better and better, and each of those little tiny transistors has gotten cheaper and cheaper. That miniaturization is the reason we have many products we take for granted today. The average car now has more than a thousand chips in it. They’re everywhere, essentially. Your light switch, your light bulb.

My light bulb?

LED light bulbs are based on a semiconductor called gallium nitride, which is basically a chip. My espresso machine, my dishwasher, they’ve all got chips.

The chip supply chain is incredibly geographically dispersed. The average chip might cross a national border 70 times before it actually reaches the final destination because there’s all these different players involved. They get fabricated in one plant and packaged in another plant and tested in another plant and shipped to a distributor. The supply chain is incredibly complicated, and a lot of it is in China.

The U.S. is certainly not lagging when it comes to inventing new and advanced chips. In fact, chip designers in the U.S. account for more than 50 percent of all semiconductor revenue globally. The issue is in the manufacturing. In 1990, the U.S. made 37 percent of the world’s chips. Thirty years later, that number has cratered to 12 percent. While the country might design some of the most advanced chips in the world, almost all the manufacturing takes place in foreign countries. What happened?

It’s a complicated story, and it’s not “We moved to Asia for cheap labor.” What first started happening is companies in Japan started making chips. In the ’80s, they started making memory chips, which are one of the most widely used chips around, and then Korea got into it. The fabrication of semiconductors is not a game about cheap labor—it’s about big expenditures on very expensive machines. Now the factories cost, say, $10 billion each, and some of the individual machines cost $200 million, and they have hundreds of these machines in some of these factories. It’s a game about money, not about labor.

Perhaps the biggest reason for why U.S. manufacturing of chips has fallen is because of one man: Morris Chang. Born in China, Chang came to the U.S., where he spent 25 years working at Texas Instruments, one of the oldest semiconductor makers in the country. Up until the ’80s, most semiconductor makers designed and manufactured their own chips in their own factories. But Chang saw an opportunity to cut costs and get more efficient.

In the late ’80s, he left Texas Instruments. With the full support of the Taiwanese government, Chang helped found Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., which makes chips that other companies design. TSMC is now the most important semiconductor manufacturer in the world, producing advanced chips for companies like Nvidia, Apple, and even Amazon.

TSMC produces more than 90 percent of the advanced chips, the things that you really care about. For example, an Apple iPhone always uses the most advanced TSMC process. They go immediately to the most advanced technology, and TSMC is the only company in the world that can make it. That’s the alarming factor.

Taiwan, though friendly to the U.S., has a fraught relationship with China.

He founded the industry in Taiwan. He’s very close to the government. He’s now almost like a government ambassador. Now, TSMC have agreed to build factories in Arizona. They recently stepped up their investment to $40 billion in Arizona, and they expect to get money under the CHIPS Act to help do that. They have a big factory already under construction north of Phoenix. There’s a long-term trend to be close to your customers, but there is added incentive with all this attention. If you’re Apple, you want TSMC making chips in Arizona.

Although then they would have to send the chips to China to assemble the phones.

Even the chips that Intel makes in Oregon or Arizona, they’re sent to Asia usually to be packaged and tested. That’s originally because that part of the business, the packaging and testing, is labor intensive. So that’s why U.S. makers started having assembly and test operations in Asia, starting in the 1970s. That is another problem for the U.S. that all assembly happens abroad.

According to the New York Times, all of this will boost U.S. production of chips from 12 percent to 14 percent, which seems disappointing.

That’s a little pessimistic. That’s not including the tax credits, the last $25 billion. But the 12 percent figure is not the important figure. The important figure is that 95 percent of advanced chips now come from Taiwan. If we get a 20 percent of the advanced chips made in America, that would be a huge thing because those are the really important chips in this discussion.

And what’s the barrier there?

If TSMC builds its factories here in America, that’s probably the most important single thing that will make that figure go down. But other players are Samsung, which is the other big foundry service company, they build almost all in South Korea. They already have a factory in Austin, Texas, but they’re putting $17 billion into a new factory in Texas, too. Intel, which used to lead in the advanced chip production, but has fallen behind in the past five years, is spending heavily to catch up in the race. So that’s another factor that’s going to reduce that 95 percent figure down.

Is the scare about the 95 percent figure mostly coming from that COVID supply chain shock where we couldn’t get the chips shipped to where they needed to be? Or is there a bigger national security concern with Taiwan dominating the manufacture of the highest-end chips?

I would say that the supply chain issues galvanized politicians. But before that was happening, the Pentagon has always worried about where the chips have come from. They’ve established this program 30 years ago to have trusted foundries—they have chip factories with armed guards around them and all these procedures. On the more strategic level, a lot of the concern is from advanced weapons systems. I mean, the U.S. wants to have its weapons be the smartest in the world, and by large they are.

It’s my understanding that you need a really highly skilled labor force to manufacture these chips. Is that going to be a hindrance here?

Very likely it will be. There’s two classes of workers that are important. There’s the actual people in the bunny suits running the machines in the factories, and they usually have a two-year community college degree. But then we need Ph.D.s in all kinds of disciplines. A lot of this is a chemical engineering process, all the things you do on wafers, but you need electrical engineers, chemical engineers, material scientists, all these people to keep the advancing miniaturization and all the things you need to do in chips, the search for new materials to make chips out of.

Something like two-thirds of the Ph.D. candidates in the disciplines that matter are foreign-born now. Since the Trump administration, it’s been very hard for those people to stay in the U.S. after they get their Ph.D.s. There’s been lots of effort to put more money into making our educational institutions stronger and graduating more people. At the same time, there’s the immigration issue. We are essentially shooting ourselves in the foot by sending these people home, where among other things, they start building chips in other countries. Many of them are Chinese and go back to China.

Underlying all this is the tension between the U.S. and China. The U.S.

government fears that if China is able to get its hands on the most advanced chips, it’ll make the tech race between the countries even more competitive, especially given China’s aggressive push into A.I. and surveillance. The U.S. placed pretty strict sanctions on China and crippled its ability to make or get a hold of the more sophisticated chips. What happened with those sanctions?

There are two poles of this. One is to stop them from buying the most advanced chips. So we’ve put restrictions on companies like Huawei. We’ve hobbled them by limiting their ability to buy advanced chips. At the same time, China has an indigenous semiconductor industry. They are like 10 years behind, but they are making many of the simple chips that people use. Basically we’re trying to freeze them in place. We used to say, “It’s OK if China is basically two generations behind in ship manufacturing technology.” These latest sanctions, which came out in October 2022, are saying, “We’re going to freeze them at about 2018. We’re not going to allow them to get the machines that allow them to get to progress beyond that.” It’s a pretty radical step up in U.S. policy. We have no idea how China is going to respond, but I think they will respond in some way we’re not going to like.

China is one of the biggest buyers of chips in the world. If you take these kinds of actions or put these sanctions in place, couldn’t they retaliate by stepping back their purchasing power or buy somewhere else?

The trouble is, let’s say they want to make a smartphone. You can’t make an advanced smartphone without a chip that comes from someplace else. So do they want to shoot themselves in the foot by making those smartphones? While we depend on China to make stuff for us, kinds of stuff, they depend on other countries to make them chips. They cannot get away from buying certain kinds of chips if they want to do surveillance of those people if they want to build super computers, if they want to do A.I. They need chips that are made by foreign companies.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.

Read Again https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiVmh0dHBzOi8vc2xhdGUuY29tL3RlY2hub2xvZ3kvMjAyMy8wMS9zZW1pY29uZHVjdG9yLWNoaXBzLWFjdC11cy1uYXRpb25hbC1zZWN1cml0eS5odG1s0gEA?oc=5Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Can the CHIPS and Science Act level the semiconductor chip playing field? - Slate"

Post a Comment